Re-design, re-look o ready-made.

Parole per rigenerare gli oggetti.

Re-design, re-look or ready-made.

Words for regenerating objects

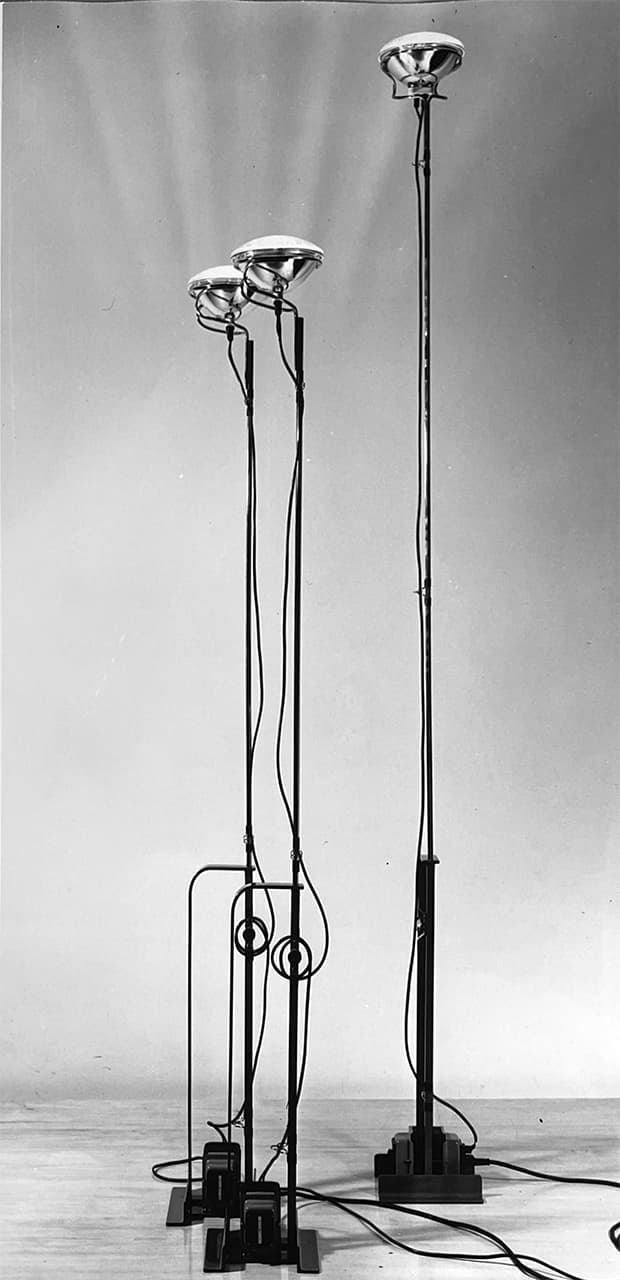

Above: Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, Toio lamp, Flos. 1962

Quante parole esistono per raccontare come si può progettare un oggetto? Una piccola matrioska di parole: li termine design – il principale, oramai – contiene quello di re-design, e questo a sua volta può occultarne altri: quello, ben più scivoloso di styling, nella sua accezione di semplice rifacimento dell’immagine, come puro e semplice relook; ma anche quello di ready-made (e tralasciamo, perché fuori luogo qui, quello legato al nuovo fare dei makers).

In riferimento al metodo progettuale dei Castiglioni, is parla di continuazione di ready-made, un metodo che viene accostato alle opere Dada e a quella di Duchamp in particolare. E certamente un soffio di dadaismo ironico e divertito circola in gran parte degli oggetti progettati dai Castiglioni. Cosi come di sicuro

vi sono riferimenti espliciti e vitali all’arte delle neoavanguardie. Ma, per me, il ready-made dei Castiglioni è tutt’affatto diverso rispetto a quello dei dadaisti. Anzi, inverso. Se Duchamp prendeva gli oggetti e il sottraeva al loro contesto, per inserirli con effetto straniante in un museo, in una galleria, nominandoli come opere d’arte, il ready-made dei Castiglioni prende oggetti da un contesto d’uso e li reinventa in un altro contesto d’uso. Sono due operazioni profondamente diverse, non solo per la finalità opposta che le ispira (sottrarre l’oggetto alla sua funzione primaria, nell’un caso; attribuire una funzione efficace all’oggetto, nell’altro), ma anche per i passaggi logico-concettuali e pratico-operativi che vi sono sottesi.

Oltre alla tradizione colta e artistica del ready-made, ne esiste poi una popolare, da bricoleur, qualcosa che può essere capitato di realizzare a ciascuno di noi. Qualche anno fa s’era vista in Italia una piccola mostra sul Design del popolo. 220 inventori della Russia post-sovietica, un repertorio straordinario di oggetti di produzione casalinga, realizzati da persone comuni sotto la spinta dell’indigenza e del bisogno: una spina che trasforma un portalampada in presa elettrica; uno zerbino per pulirsi le scarpe composto da una distesa di tappi corona; un rullino da pittura realizzato con li cilindro di gommapiuma dei bigodini; un attrezzo per massaggiare la schiena ricavato da un abaco in legno; un tappo per la vasca da bagno fatto con un tacco di gomma e una forchetta…

Fantasmi di prodotti irraggiungibili perché troppo cari o perché proibiti, questi oggetti testimoniano della particolare capacità umana che Richard Sennett, nel suo libro L’uomo artigiano, ci descrive come abilita correttiva, ovvero la capacità di trasformare in modo sostanziale gli oggetti esistenti. Non siamo di fronte a un semplice assemblaggio, a una riparazione che si limita a riportare l’oggetto al suo stato precedente, a un approccio statico che non produce alcuna trasformazione. Si tratta invece di un salto intuitivo che mette in azione curiosità e abilità correttive in grado “di modificare la forma e la funzione dell’oggetto una volta ricomposto” di un’azione dinamica, che produce autentica innovazione, trasformazioni sostanziali, compresi gli spostamenti di dominio. Ovvero il passaggio da un ambito di applicazione ad un altro. È quello che ha fatto il netturbino Vladimir Archipov, trasformando in badile il cartello stradale triangolare di segnalazione di lavori in corso, su cui campeggia l’icona di un uomo che scava: ‘Beh, io stavo caricando dell’immondizia nel camion quando ho trovato questo cartello stradale. Stavo per buttarlo, ma poi ho sentito che era davvero leggero. Ehi, ho pensato, sarebbe fantastico per spalare la neve, d’inverno. Ci davano dei badili del cazzo, totalmente inutili, quindi ho deciso di fabbricarmene uno per conto mio. Ho segato due angoli, oppure li ho spezzati e ho piegato il terzo. L’ho forato, ho inchiodato un angolo su se stesso per rinforzarlo e ci ho infilato il manico. Ed ecco fatto li badile, è cosi che lavora il vero operaio’.

Certo, nel lavoro dei designer c’è molto anche di questa intuizione. Ma li design è un’attività ben più complessa, che non può affidarsi soltanto alla mossa progettuale da scacco al re.

È una professione emersa con la rivoluzione industriale, la meccanizzazione, i nuovi materiali e il mercato, ma che mantiene un forte legame con la lunga storia della trasformazione degli oggetti. Ogni nuovo tavolo o sedia o coltello, ogni nuovo

martello o pinza o badile non sono che rielaborazioni, spesso minimali, di archetipi formatisi nel tempo. Un corteo lungo millenni di oggetti e azioni, che da un numero limitato e scarno si è sviluppato in infinite varianti culturali, dalle forme più semplici fino a quelli che pochi virtuosi hanno saputo trasformare in opere d’arte. Fino all’avvento del design, è stata questa tradizione artigiana, sapiente dei materiali e padrona delle tecniche, a realizzare la trasformazione delle cose. Cose apparentemente uguali a se stesse, ma ciascuna in realtà con un proprio carattere distintivo: un certo modo di trattare i materiali, una certa capacità di conferire grazia all’ornamento, una certa abilità nel rendere più robusta la struttura, e via dicendo.

Quando sono nati oggetti del tutto nuovi (lampade elettriche, macchine fotografiche, frigoriferi, treni, automobili, macchine per scrivere, telefoni, computer, cellulari e via enumerando), una volta fissata la loro fisionomia, il mestiere del designer è quello di ri-disegnare. Dunque il designer rielabora di oggetti stabilmente inseriti nel mondo quotidiano, quando gesti e comportamenti si fanno ripetitivi e quasi indifferenti. Ma anche quando rielabora oggetti più complessi o quando si trova a maneggiare nuovi materiali, nuove tecnologie, nuovi comportamenti.

A mio parere un progetto di design, anche li più brillante e innovativo, è quasi sempre un’attività di re-design: progettare a partire da oggetti che già si trovano, interamente o in parte, sul mercato, fra i prodotti o le componenti nei più diversi

settori d’impiego. E dunque, nella progettazione di design, li ready-made è una variante nobile del re-design. E un ready-made che combina la tradizione delle avanguardie artistiche e quella popolare del bricolage con le competenze sempre più raffinate del design (ideazione, progetto, disegno, modello, prototipo, confronto con la produzione e i tecnici di fabbrica, li mercato, il pubblico, gli utenti…).

È questa attività complessa che si intuisce in progetti che hanno alla base un’idea di ready-made, come lo sgabello Mezzadro (1957, poi Zanotta, 1971), in cui c’è lo spostamento di un oggetto da un ambito a un altro, dal sedile del trattore alla seduta per al casa; la lampada da terra Toio (Flos, 1962), risultato di un processo di assemblaggio, in cui li faro di automobile di provenienza americana è usato invece qui come fonte illuminante per appartamenti; o la più tarda lampada da ripiano o parete Lampadina (Flos, 1972,) nella quale li ready-made riguarda specialmente la base, che richiama una bobina cinematografica, ma che serve per arrotolare il cavo e per appendere la lampada a muro.

Pier Giacomo e Achille Castiglioni non sono i soli ad utilizzare questa tecnica, che è anzi tipica del design italiano. Fra i tanti esempi, si possono ricordare la lampada Faulkner (Danese, 1964) di Bruno Munari, ottenuta da un tessuto elastico

tubolare preso dall’industria delle calze, o il ripiano in cristallo che Gae Aulenti appoggia su quattro ruote industriali ricavandone un tavolino (Fontana Arte, 1980). Tuttavia è soltanto nel lavoro dei fratelli Castiglioni che questa modalità progettuale acquista il carattere di una metodologia, o se preferite di una poetica.

Ecco, mi sbaglierò, ma vorrei provare ad accostare gli oggetti dei Castiglioni all’opera di un poeta francese come Francis Ponge, surrealista sui generis, esistenzialista malgré lui, che affidava alle cose concrete li compito di rifondare non solo il linguaggio, ma persino le emozioni. Lo ha scritto molto bene Italo Calvino (sul Corriere della Sera del 29 luglio 1979), commentando l’edizione italiana del libro Le parti pris des choses del1949, a partire da uno dei più banali e usuali oggetti analizzati da Ponge: la porta. “Questo breve testo si intitola I piaceri della porta ed è un buon esempio della poesia di Francis Ponge: prendere un oggetto il più umile, un gesto il più quotidiano. E cercare di considerarlo fuori d’ogni abitudine percettiva, di descriverlo fuori d’ogni meccanismo verbale logorato dall’uso. Ecco che una cosa indifferente e quasi amorfa come una porta rivela una ricchezza inaspettata; siamo tutt’a un tratto felici di trovarci in un mondo

pieno di porte da aprire e da chiudere. E questo non per una ragione estranea al fatto in sé (come potrebbe essere una ragione simbolica, o ideologica, o estetizzante), ma solo perché ristabiliamo un rapporto con le cose come cose, con la diversità d’una cosa dall’altra, e con la diversità d’ogni cosa da noi. Improvvisamente scopriamo che esistere potrebb’essere un’esperienza molto più intensa e interessante e vera di quel distratto tran-tran in cui si è incallita al nostra mente”.

I piaceri della porta. E. Ponge

I re non toccano le porte.

Non conoscono questa felicità:

spingere davanti a sé piano piano o bruscamente uno

di quei grandi riquadri familiari,

voltarsi indietro per rimetterlo a posto,

tenere una porta tra le braccia […]

La felicità di impugnare al ventre,

per il suo nodo di porcellana,

un di quegli alti ostacoli d’una stanza;

il rapido corpo a corpo in cui il passo si trattiene l’i-

stante che basta perché l’occhio s’apra

e il corpo intero si adatti alla nuova dimora […]

Con mano amica la trattiene ancora,

prima di respingerla deciso e rinserrarsi

cosa di cui lo scatto della molla potente

ma ben oliata gradevolmente l’assicura.

Se provate a sostituire qualche parola qua e là non vi sarà difficile ritrovare, pari pari, la poetica del fare tipica dei Castiglioni, un metodo di progetto che suona come controcanto alle parole dello stesso Ponge, tratte dal suo Méthodes del 1961: “È con facilità che vorrei si entrasse in ciò che scrivo. Che ci si trovasse a proprio agio. Che si trovasse tutto semplice. E però che tutto fosse nuovo, inaudito: illuminato con naturalezza, un nuovo mattino”.

La facilità, l’agio, la semplicità, nel loro stridore con quell’aggettivo – inaudito -, sono in perfetta assonanza con quanto tante volte abbiamo letto e visto dei Castiglioni, con l’’allegria materialista’ (l’espressione è di Jacqueline Risset) che pervade per esempio tutti i sedili, da Mezzadro, a Sella, a Allunaggio, e lampade come Snoopy. La stessa naturalezza ed essenzialità di lampade ‘inaudite’ come Toio, Luminator e Arco.

‘Guardi questa lampada, la Luminator – racconta Achille in un’intervista apparsa sul blog www.in-visibile.it – Ecco, secondo noi meno di cosi non si poteva fare, è un tubo a tre gambe con una lampadina messa sopra. Quest’essenzialità è quella che fa l’oggetto, che crea un rapporto di reciproca simpatia tra chi l’adopera e chi l’ha progettato’.

E siamo tutt’a un tratto felici di trovarci in un mondo pieno di lampade da accendere e spegnere, da spostare, da appendere…

Raimonda Riccini, Archtetto

Anno 2013

How many words are there that describe ways in which we can design an object? A little matryoshka of words: the term design – the main one these days – contains that of re-design, and this in turn can conceal others: the far more slippery ‘styling’, in its sense of simply remaking an image, like the pure and simple ‘re-look’; but also that of ‘ready-made’ (and the new ‘makers’, which we can only touch on in passing, since it is out of scope here).

Regarding the Castiglioni design method, there is constant talk of ready-made, a method closely associated with the Dada movement and the work of Duchamp in particular. And most of the objects designed by the Castiglionis certainly have an ironic and fun Dadaist air about them. As well as clear and lively references to the art of the Neoavanguardia. But for me, the Castiglionis’ ‘ready-made’ is completely different from that of the Dadaists. The opposite, in fact. While Duchamp took objects and removed them from their context, placing them in museums or galleries to strange effect, calling them works of art, the Castiglionis’ readymade takes objects from a practical context and reinvents them in another practical context. They are two profoundly different operations, not only because their relative purposes are the opposite of each other (to remove an object from its primary function, in one case; to attribute an effective function to the object, in the other), but also because of the logical-conceptual and practical-operational steps underlying them.

In addition to the cultured and artistic tradition of readymade, there is also a popular one: that of bricolage, something each of us might have dabbled in ourselves. A few years ago, a small exhibition was held in Italy called Design del popolo. 220 inventori della Russia post-sovietica (‘People’s design: 220 inventors from post-soviet Russia’). It showcased an extraordinary repertoire of home-made objects, made by ordinary people driven by poverty and need: a plug that turns a lamp holder into an electrical socket; a doormat to clean your shoes consisting of an expanse of beer crowns; a paint roller made from the foam cylinder of hair rollers; a back massage tool made from a wooden abacus; a bath plug made from a rubber heel and a fork…

Ghosts of products that were unattainable because they were too expensive or forbidden, these objects testify to the particular human ability that Richard Sennett, in his book ‘The Craftsman’ describes as the corrective ability, or the ability to substantially transform existing objects. This is not mere assembly; a repair that simply returns the object to its previous state, a static approach that does not produce any transformation. Instead, it is an intuitive leap that puts curiosity and corrective skills into action and can ‘change the shape and function of the object once it is reassembled’ though dynamic action, which produces genuine innovation and substantial transformation, including changes of context. That is, the transition from one field of use to another.

This is what Vladimir Archipov did, turning a triangular ‘men at work’ road sign into a shovel, bearing the image of a man digging: ‘Well, I was loading garbage onto the truck when I found this road sign. I was going to throw it away, but then I felt how light it was. Hey, I thought, that’d be great for shovelling snow in the winter. The shovels they gave us were good for nothing, so I decided to make my own. I sawed off the two corners, or I broke them, and I bent the third. I pierced it, I bolted a corner onto itself to reinforce it, and put the handle on it. And there you have a shovel. That’s how a real worker works.’

Of course, there’s a lot of this intuition in the work of designers. But design is a far more complex task that requires more than a strategic chess move.

It is a profession that emerged with the industrial revolution, mechanization, new materials, and the market, but that maintains a strong link with our long history of transforming objects. Every new table, chair or knife, every new hammer, shovel or set of pincers is nothing more than a reworking, often minimal, of archetypes formed over time. A procession of thousands of years of objects and actions which, from a limited and scarce number, has developed into infinite cultural variations, from the simplest forms to those that a few talented people have transformed into works of art. Before the advent of design, it was this artisan tradition, this mastery of materials and techniques, that came into play in the building and altering of things. Things seemingly the same as each other, but each with their own distinctive character: a certain way of treating materials, a certain ability to instil grace in a decoration, a certain ability to make a structure more robust, and so on.

When completely new objects are born (electric lights, cameras, refrigerators, trains, cars, typewriters, phones, computers, cell phones and so on), once their general form is established, the designer’s job is to re-design them. So the designer reworks objects that are permanently embedded in the everyday world, when gestures and behaviours become repetitive and almost indifferent. But also when they rework more complex objects or when handling new materials, new technologies, and new behaviours.

In my opinion, a design project, even the most brilliant and innovative, is almost always a re-design activity: design based on objects that are already, wholly or partly, on the market, among products or components in the most disparate sectors. And so, in design, ready-made is a noble variant of re-design. It is a ready-made that combines the tradition of the artistic avant-garde and the popular tradition of bricolage with the increasingly refined skills of design (conception, planning, design, model, prototype, collaboration with manufacturing and fabrication technicians, the market, the public, users and so on).

This complex activity is discernible in projects that are based on an idea of readymade, such as the Mezzadro stool (1957, then Zanotta, 1971), where an object is transposed from one setting to another, from the tractor seat to the domestic chair; the floor lamp Toio (Flos, 1962), the result of an assembly process in which an American car headlight is re-purposed as a domestic light source; or the later shelf lamp or wall lamp Lampadina (Flos, 1972), in which the ready-made aspect relates particularly to the base, which looks like a roll of film but is used for winding up the cable and hanging the lamp on the wall.

Pier Giacomo and Achille Castiglioni were not the only ones to use this technique: indeed it is typical of Italian design. Among the many examples, we can mention the Faulkner lamp (Danese, 1964) by Bruno Munari, made using tubular elastic fabric taken from the hosiery industry, or the plate-glass shelf that Gae Aulenti rested on four industrial wheels to create a small table (Fontana Arte, 1980). However, it is only in the hands of the Castiglioni brothers that this design mode became a methodology, or if you prefer, a form of poetry.

Well, I may be wrong, but I would like to try to compare objects designed by the Castiglionis with the work of a French poet like Francis Ponge, the unique surrealist and existentialist malgré lui, who entrusted objects with the task of rebuilding language and even emotion as well. Italo Calvino put it very well (in the Corriere della Sera newspaper on 29 July 1979), in his commentary on the Italian edition of the 1949 book Le parti pris des choses, regarding one of the most banal and day-to-day objects analysed by Ponge: the door. ‘This short text is called The pleasures of the door and is a good example of Francis Ponge’s poetics: taking a most humble object, a most mundane gesture. And trying to consider it removed from any perceptual habit, to describe it without leaning on any worn-out verbal mechanism. In this way, an indifferent and almost amorphous thing like a door reveals unexpected wealth; we are all of a sudden happy to find ourselves in a world full of doors to open and close. And this is not for a reason foreign to the object itself (as a symbolic, ideological, or aestheticizing reason might be), but only because we re-establish a relationship with things as things, with the differentness of one thing from another, and with the differentness of everything from us. Suddenly we find that existence can be a much more intense, interesting and real experience than the humdrum one in which our mind has become embroiled.’

The Pleasure of the Door F. Ponge

Kings never touch doors.

They’re not familiar with this happiness:

to push, gently or roughly before you

one of these great, friendly panels, to turn towards it to put it back in place—to hold a door in your arms.

The happiness of seizing one of these tall barriers to a room

by the porcelain knob of its belly;

this quick hand-to-hand, during which your progress slows for a moment,

your eye opens up and your whole body adapts to its new apartment.

With a friendly hand you hold on a bit longer,

before firmly pushing it back and shutting yourself in—of which you are agreeably assured by the click of the powerful, well-oiled latch.

[translation by C. K. Williams].

If you replace a few words here and there, it would not take long to find the poetics of the Castiglionis’ typical approach: a method of design that sounds like a counterpart to the words of Ponge himself, taken from his Methodes of 1961: ‘I would like you to find my writing approachable. I would like you to be comfortable. To find everything simple. And yet all new, unprecedented: naturally illuminated, like a new day.’

Ease and simplicity stridently expressed alongside that adjective ‘unprecedented’ are in perfect harmony with what we have read and seen so many times from the Castiglionis, with the ‘materialist joy’ (to use Jacqueline Risset’s term) that pervades, for example, all their chairs, from Mezzadro, Sella and Allunaggio, and lamps such as Snoopy. The same naturalness and essentiality of ‘unprecedented’ lamps such as Toio, Luminator and Arca.

‘Take this lamp, the Luminator’ – said Achille in an interview on the blog www.in-visibile.it. ‘Well, in our opinion, anything less than that would be impossible. It is a tube with three legs and a bulb placed on top. This essentiality is the what makes the object, what creates a relationship of mutual sympathy between those who use it and those who designed it.’

And all of a sudden we are happy to find ourselves in a world full of lamps to turn on and off, to move, to hang…

Raimonda Riccini, Architect

Year 2013